Apple's AI Game is Misunderstood

It is betting on on-device inference

Note: a few hours after publishing this piece, I came across news that Apple acquired Q.ai, an Israeli startup which provides AI-powered voice processing for devices. This confirms what I argue below, which is that Apple’s view is that on-device intelligence processing is their ambit.

Apple’s AI strategy has become a Rorschach test for the technology industry. Critics see a company falling dangerously behind. Needham analyst Laura Martin claims it is one to two years behind its competitors. But almost all of this commentary, whether bullish or bearish, focuses on the wrong question.

The standard narrative compares Apple’s AI capex to Microsoft’s, Apple’s Siri to Google’s Gemini, Apple’s foundation models to OpenAI’s GPT-4. By these metrics, Apple looks behind. But these comparisons assume Apple is trying to win the same race. The evidence suggests it isn’t.

Apple is betting that on-device inference wins for average consumers over time. This bet has structural economics that external commentary consistently ignores, which economics could make the capex gap irrelevant.

The Pundit Case: Apple Is Losing

The bearish consensus on Apple’s AI position has crystallized around a few key concerns, and the commentary has been remarkably consistent across analysts, journalists, and tech strategists.

Ben Thompson at Stratechery has been perhaps the most thorough chronicler of Apple’s AI struggles. In April 2025, after Apple delayed its “personalized Siri” indefinitely, Thompson declared that “the most ambitious Apple Intelligence features on display at WWDC last June not only haven’t shipped to date, but in a twist that’s equal parts embarrassing and concerning, they won’t ship until next year at the earliest.” John Gruber, the closest thing Apple has to an official court chronicler, titled his own assessment Something Is Rotten in the State of Cupertino.

Thompson’s deeper analysis draws an uncomfortable parallel to Microsoft’s fumbling of mobile. “Apple’s absolutist and paternalistic approach to privacy have taken all of these options off the table,” he writes, “leaving the company to provide platform-level AI functionality on its own with a hand tied behind its back, and to date the company has not been able to deliver.” The kicker: “given how different AI is than building hardware or operating systems, it’s fair to wonder if they ever will.”

Wall Street analysts have echoed these concerns. TD Cowen’s Krish Sankar wrote in July 2025 that “the incomplete AI strategy is still the biggest overhang” on Apple shares. JPMorgan’s Samik Chatterjee set expectations for a “lackluster” WWDC. Apple stock was down over 15% year-to-date as of mid-2025, the second-worst performer among the Magnificent Seven.

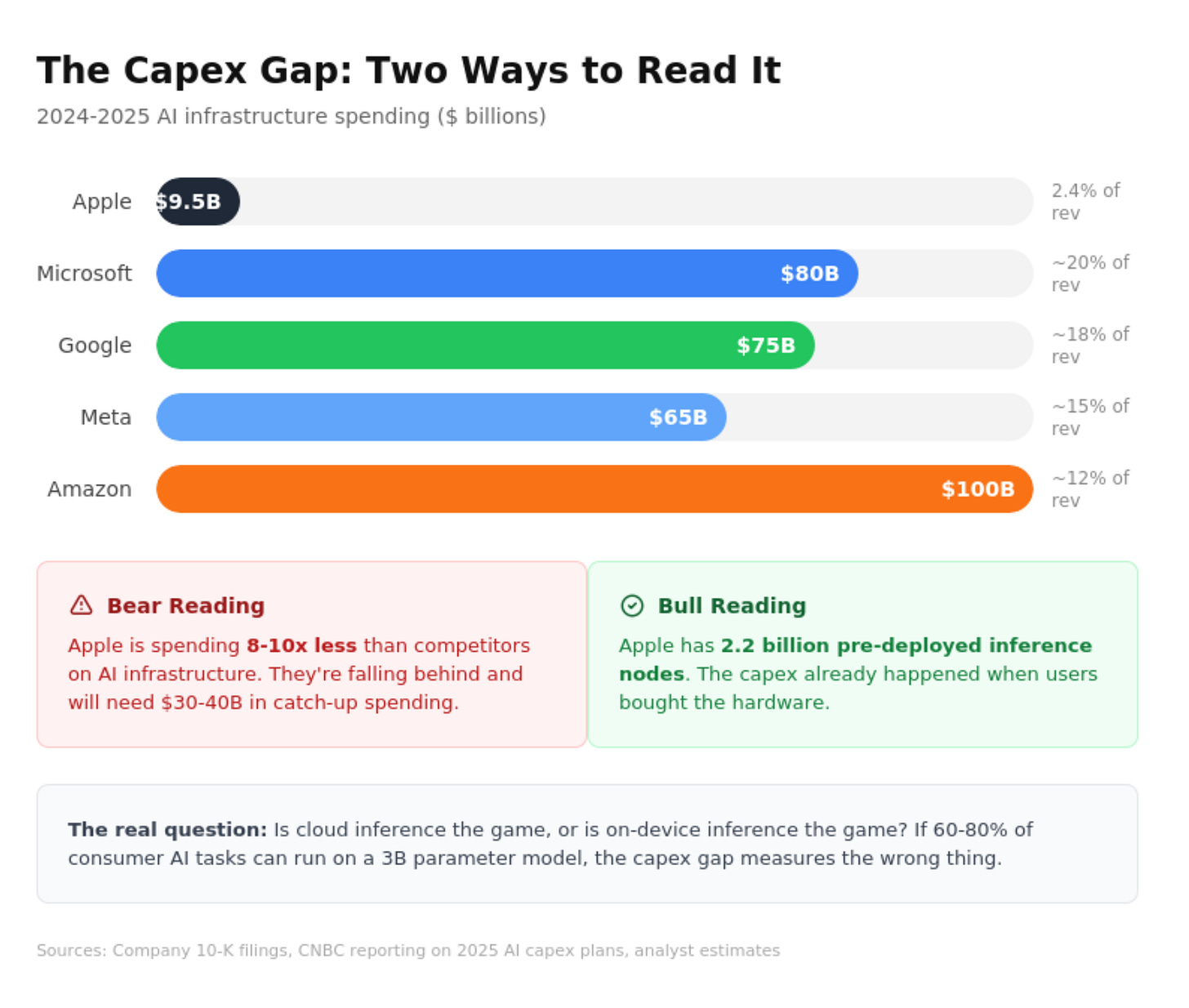

The capex gap has become the central exhibit in the prosecution’s case. Apple spent $9.5 billion on capital expenditures in fiscal 2024, which is about 2.4% of revenue. Microsoft alone is spending around $80 billion in 2025, approximately 20% of revenue, on AI-focused infrastructure. Microsoft, Amazon, Google, and Meta are collectively planning over $300 billion in AI infrastructure spending in 2025. Some analysts suggest Apple needs a “catch-up” plan of $30-40 billion by 2026 just to remain competitive.

The Siri delay has become symbolic shorthand for Apple’s broader struggles. The company announced in December 2025 that next-generation Siri wouldn’t arrive until 2026, with marketing chief Greg Joswiak explaining that Apple “didn’t want to disappoint customers.” The irony wasn’t lost on observers.

What the Pundits Miss: On-Device Economics

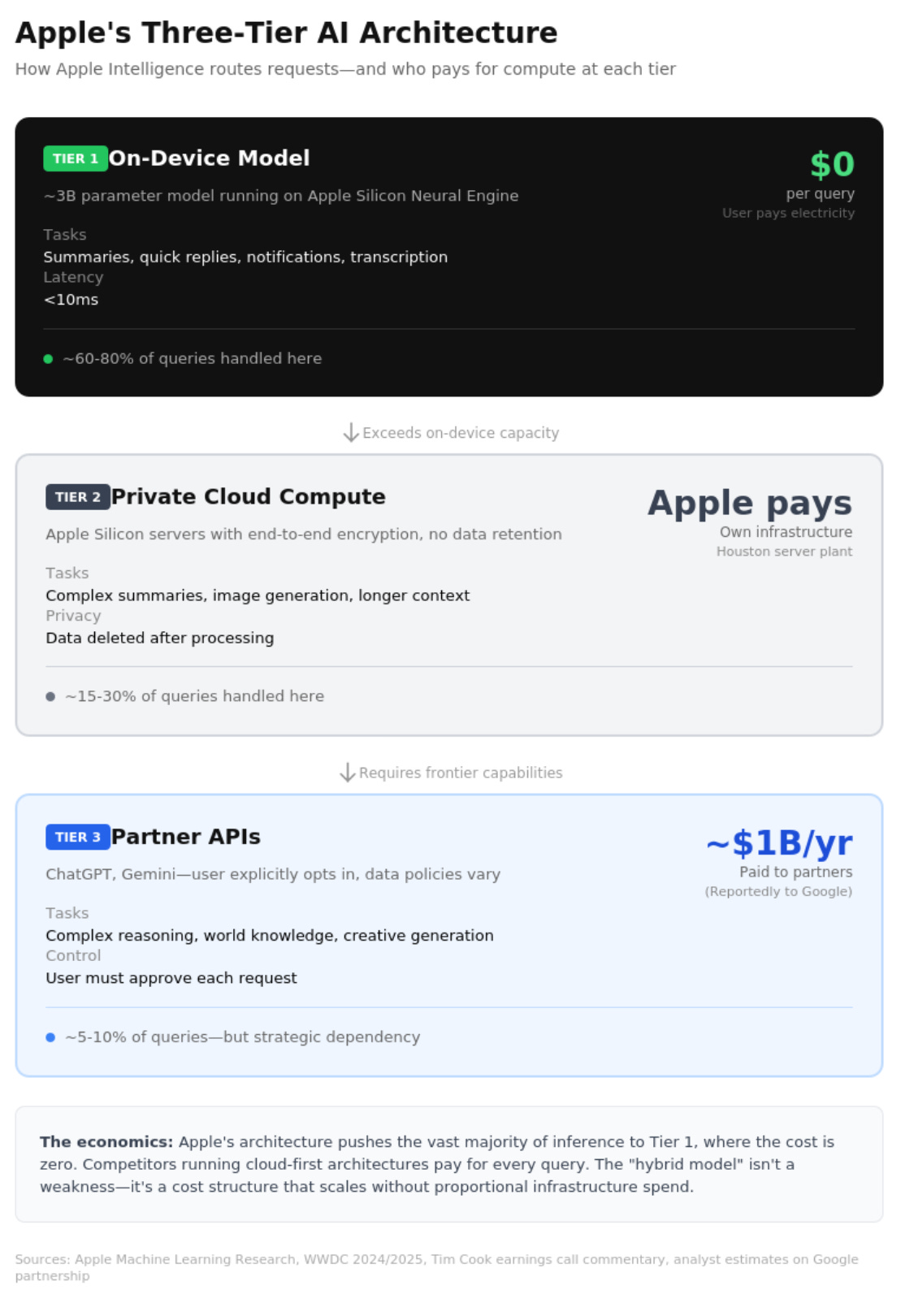

Given this, it is clear that Apple isn’t trying to win the cloud AI race. It’s betting on a different architecture entirely, where inference happens on the device, not in the datacenter.

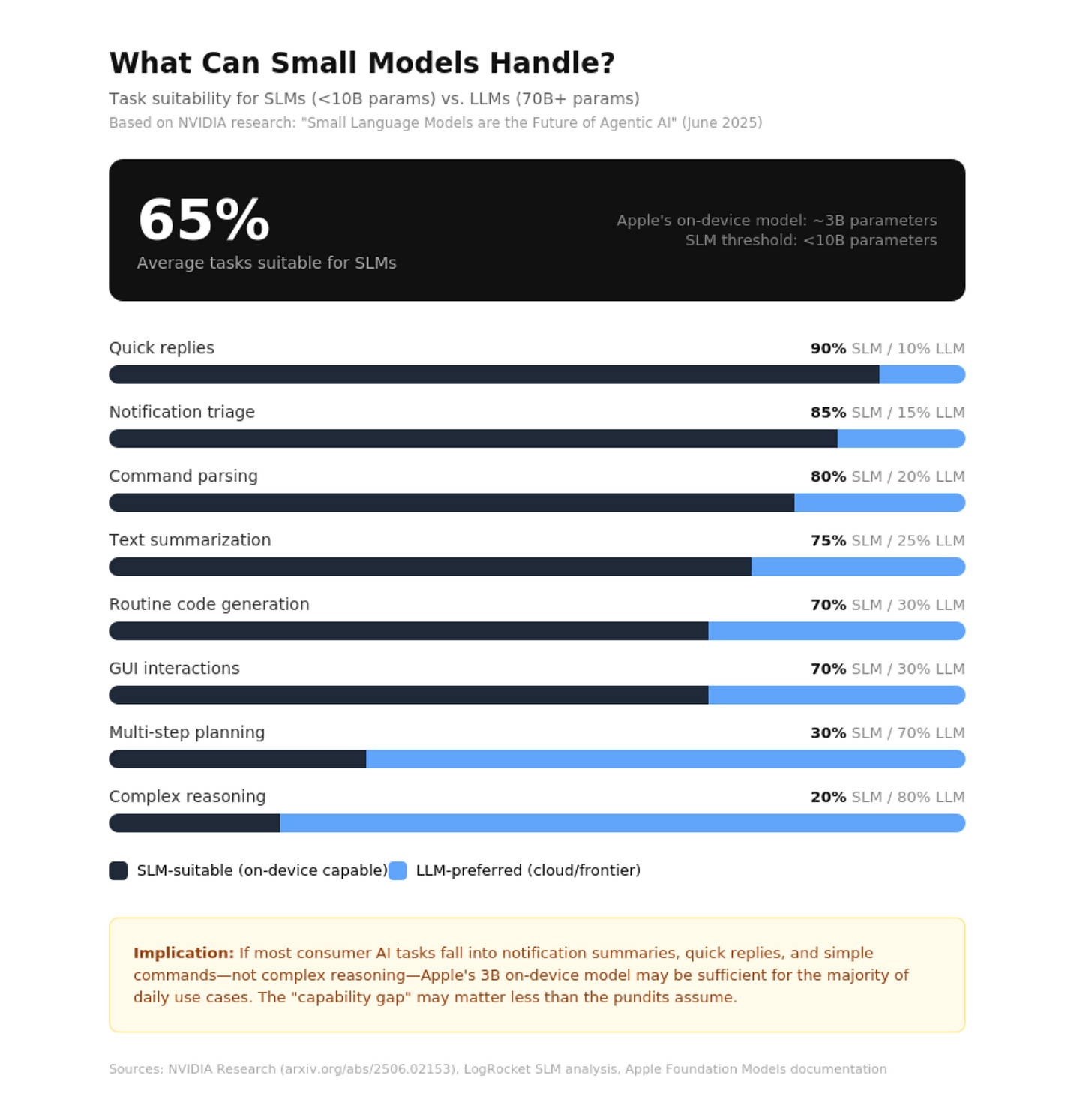

This isn’t crazy. A June 2025 position paper from NVIDIA researchers, who don’t have an incentive to downplay cloud GPU demand, argued that “small language models are the future of agentic AI.” Their core claim: models under 10 billion parameters are “sufficiently powerful, inherently more suitable, and necessarily more economical” for most real-world AI tasks. Serving a 7B model is 10-30x cheaper in latency, energy consumption, and compute than serving a 70-175B model.

Apple’s ~3 billion parameter on-device model sits squarely in this category. And the economics are striking.

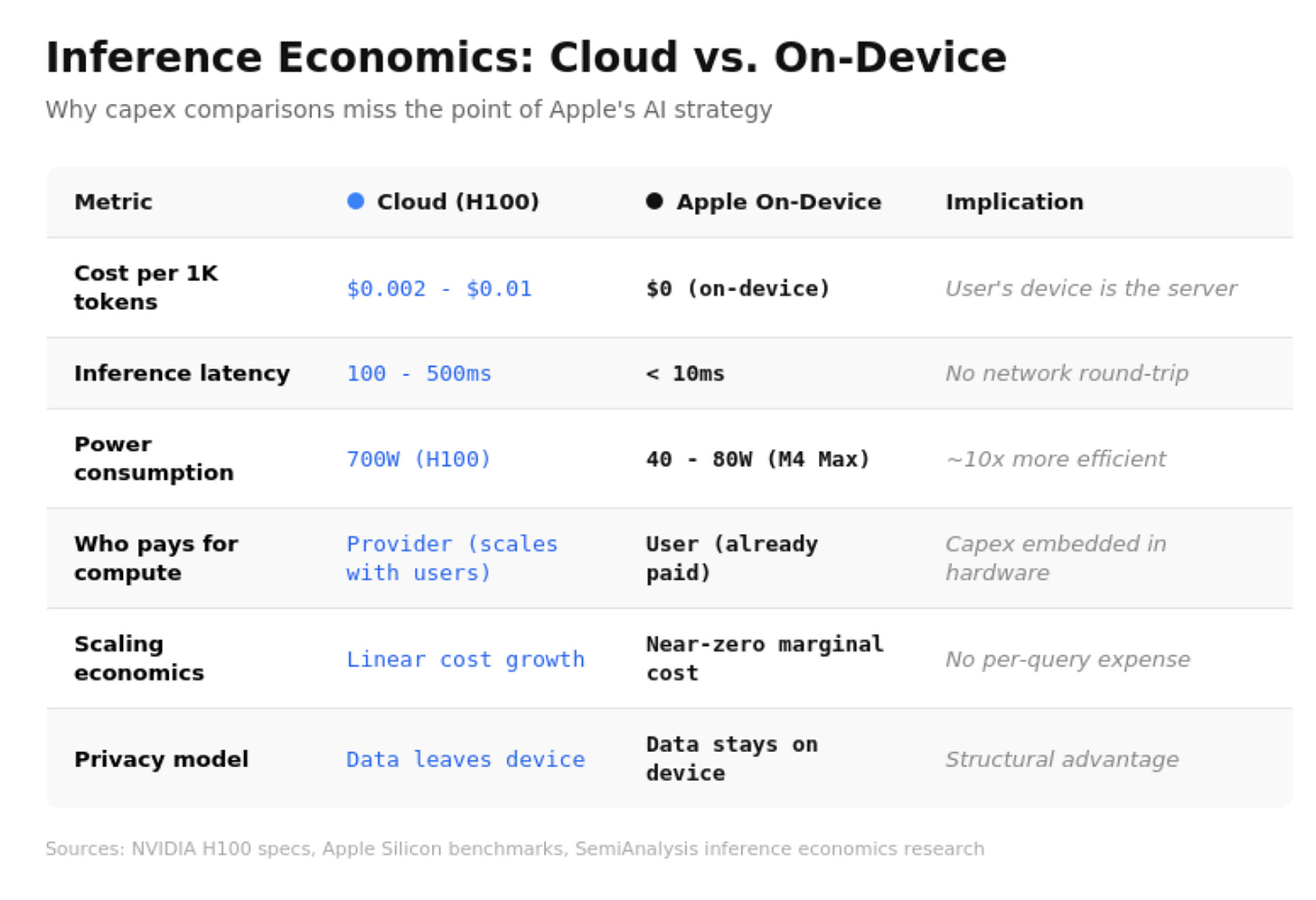

Zero inference cost. When a developer builds an AI feature using Apple’s Foundation Models framework, the inference runs on the user’s device. No API calls. No per-token charges. No cloud compute bill that scales with usage. (I recently wrote about this in the context of AI causing SaaS margins to collapse.) Developers incur zero inference costs with on-device inference. This is a game-changing proposition compared to building on OpenAI’s API or Google Cloud, where inference bills can become the dominant operating expense for AI-native applications.

To put this in perspective: OpenAI reportedly spends approximately 50% of revenue on Azure compute costs. Cloud inference economics scale linearly with users: every additional query costs money. Apple faces no such problem. The user’s iPhone is the inference server, and Apple already sold it to them. The marginal cost of serving the billionth Apple Intelligence query is approximately zero.

Pre-deployed infrastructure. The capex gap looks different when you realize Apple’s 2.2 billion active devices are the inference infrastructure. The capital expenditure already happened: it was the iPhone and Mac purchases. Apple doesn’t need to build datacenters to serve inference to a billion users; they’re serving themselves.

This is the inverse of the hyperscaler model. Microsoft, Google, and Amazon are building massive GPU clusters and then trying to fill them with paying customers. Apple has already “filled” its inference capacity by selling hardware. The AI capability is a software update to infrastructure that exists.

Energy economics. An M3/M4 Max system consumes 40-80W under AI load. An RTX 4090 consumes up to 450W. An H100 consumes 700W. For the same inference task, Apple Silicon uses roughly one-tenth the power of datacenter GPUs, and the user pays the electricity bill, not Apple.

For latency-sensitive consumer tasks, such as summarizing notifications, transcribing voice memos, or generating quick replies, on-device inference is faster. No network round-trip. No queuing behind other users’ requests. Apple’s on-device model achieves latency under 10 milliseconds for many tasks, with token generation speeds of 30-40 tokens per second on quantized models.

The Small Language Model (SLM) market is real. The SLM market is projected to grow from $0.93 billion in 2025 to $5.45 billion by 2032, which is a 28.7% CAGR. Edge computing spending is expected to reach $378 billion by 2028. Gartner projects that 75% of enterprise data will be processed at the edge by 2025. The hybrid cloud-edge consensus emerging among enterprise architects is that you train models in the cloud and deploy most inference to the edge. And, this is exactly what Apple has built.

Privacy as structural advantage. Data never leaves the device for most tasks. Competitors offering cloud-based AI must either accept privacy criticism or build comparable on-device capabilities, which requires the kind of vertical integration Apple has spent a decade developing with Apple Silicon.

The relevant question here is what percentage of consumer AI tasks can be handled by a well-optimized 3B parameter model running on Apple Silicon? NVIDIA’s research suggests 60-80% of agentic AI tasks could be handled by SLMs. If that’s true for consumer use cases, Apple’s strategy looks less like falling behind and more like building a different kind of moat.

What Apple’s Filings Actually Say

Apple’s regulatory filings are consistent with this interpretation, though they don’t articulate it directly.

In the company’s fiscal 2024 10-K, there is no dedicated discussion about AI in the Business Description. The company describes itself as designing, manufacturing, and marketing “smartphones, personal computers, tablets, wearables and accessories.” This is a hardware and services company.

Where AI does appear is in the Risk Factors section:

“The introduction of new and complex technologies, such as artificial intelligence features, can increase these and other safety risks, including exposing users to harmful, inaccurate or other negative content and experiences.”

This is AI as regulatory and product liability risk, not as growth driver. The legal team’s fingerprints are all over this language.

The financial picture tells the same story. Apple spent $110 billion on buybacks and dividends in fiscal 2024, nearly twelve times its $9.5 billion in capital expenditures. There’s no AI-specific revenue disclosure, no AI capex breakdown, no Apple Intelligence adoption metrics. This is not the disclosure profile of a company betting the farm on cloud AI infrastructure.

On earnings calls, management has defended the capex gap with what CFO Kevan Parekh calls a “hybrid model”. This is a mix of owned datacenters and third-party cloud providers. “Our CapEx numbers may not be fully comparable with others,” he explained. Tim Cook’s language on AI’s commercial impact is hedged: Apple Intelligence is “a factor” in iPhone purchases, and he’s “bullish on it becoming a greater factor.”

This is consistent with a company that sees AI as an incremental feature enhancement, not an existential strategic pivot. Whether that’s the right posture depends entirely on whether the on-device inference bet pays off.

The Open Questions

The on-device thesis has real vulnerabilities that Apple’s filings don’t address.

Partnership dependency. Apple reportedly pays Google around $1 billion annually for Gemini integration. The ChatGPT partnership economics are undisclosed. For tasks that exceed on-device capabilities, Apple is renting frontier AI from potential competitors. The recent reporting that Apple is shifting from ChatGPT to Gemini illustrates this dependency. Apple’s AI strategy is, in some meaningful sense, Google’s AI strategy. And Google runs Android.

What if frontier capabilities matter more? The on-device thesis assumes most consumer tasks can be handled by small models. But if AI capabilities continue advancing rapidly, Apple’s 3B parameter model may not be sufficient, and the company will face the build-or-rent dilemma all over again.

Adoption metrics are absent. Apple announced targeting 250 million devices with AI capabilities by end of 2025. But what percentage of users actually engage with Apple Intelligence features? What’s the retention pattern? These metrics would tell us whether on-device AI is driving value or sitting unused.

The Siri problem is real. Even if on-device inference is economically superior for routine tasks, the user-facing manifestation of Apple’s AI (Siri) is demonstrably worse than competitors. Thompson is right that this matters for perception, even if it doesn’t immediately impact iPhone sales.

The Investment Question

The gap between “Apple is behind on AI” and “Apple is playing a different game” is where investment risk lives.

The external narrative says Apple needs to spend massively on cloud infrastructure to compete. The threat is that Android plus Gemini will erode the iPhone moat, and that AI-native devices could eventually challenge Apple’s hardware dominance.

The on-device counternarrative says Apple has pre-positioned 2.2 billion inference nodes, offers developers zero-cost AI integration, and is betting on a market structure where small models handle most consumer tasks.

Both narratives have merit. Apple may be strategically exposed if frontier AI capabilities become essential to consumer expectations. But Apple may also be structurally advantaged if the SLM thesis plays out and most AI value accrues at the edge rather than in the cloud.

What’s clear is that the pundit consensus, that Apple is one to two years behind and needs to catch up on capex, ignores the on-device economics entirely. It compares Apple to Microsoft and Google on metrics that assume cloud inference is the game. If on-device inference is the game, those comparisons are asking the wrong question.

Apple’s 10-K tells you what the company is: a hardware and services business with 46% gross margins, $95 billion in annual buybacks, and AI mentioned primarily as a regulatory risk. The punditry tells you what Apple should be: a cloud AI company spending tens of billions on datacenter infrastructure.

The on-device thesis offers a third interpretation: Apple is building a moat where inference is free, privacy is structural, and the capex already happened when users bought the hardware.

Which version is right will determine whether Apple’s stock is undervalued, fairly priced, or a value trap. The market is pricing something in between. The next three years will tell us whether that’s wisdom or complacency.

If you enjoy this newsletter, consider sharing it with a colleague.

I’m always happy to receive comments, questions, and pushback. If you want to connect with me directly, you can:

I've been using Substack for a few months now and this is BY FAR the most interesting article I've read. It does a great job explaining overlooked points and links to resources that dive deeper into small language models (I think this opens a new world). Seeing all the Mac mini photos floating around Twitter it felt like people were just going numb and following the crowd (which could be true). But this piece made me realize Apple's moat in AI.

I am betting heavily on this thesis with my own application, which uses AI on-device, and I’m going to link to your work on my marketing site - thank you